Fleeing ISIS

The Situation of Aramaic-Speaking Christians

in the Nineveh Plain after ISIS

Fleeing ISIS

Aramaic-Speaking Christians in the Nineveh Plains after ISIS

Paper By

Archimandrite Emanuel Youkhana

Duhok, Iraqi Kurdistan

Archimandrite Emanuel Youkhana

Excluding the Armenians[1] and some small groups of converts[2], the Iraqi Christians are the indigenous people of Iraq. Their roots go back thousands of years before Christianity in the lands of Mesopotamia.

In other words, I believe the Iraqi Christians are the true native people of Iraq, being descendants of the ancient Assyrians and Babylonians. The Aramaic-speaking Christians (Assyrians, Chaldeans, Chaldo-Assyrians) are not a new Christian community ‘evangelised’ by western missionaries, as is the case in many African and East Asian Christian communities.

Christian religion began to come to Iraq already in the first two centuries after Christ under the rule of the Parthians, ‘who were open to the practice of different religions and seem to have tolerated the introduction of Christianity into their empire.’[3] Aramaic Christians in Iraq and their churches go back to the first generations who adopted Christianity through Jesus Christ’s apostles. Their Christianity is older than European Christianity, and their existence in Iraq predates Islam in Iraq.

The ethnic and cultural identity of Iraqi Christians

The Iraqi Christians belong to various churches and denominations, but they share a common ethnicity and culture. They speak the eastern dialect of Syriac, which is the local language that descended from Aramaic, the language spoken by Jesus Christ.

However, many Iraqi Christians who lived in big cities such as Baghdad, Mosul and Basra long ago abandoned and forgot their mother language and began speaking Arabic, due to political pressure and persecution. Nevertheless, they still believe they are not Arabs and have therefore kept their mother tongue, Syriac, as the mains language of their religious rituals.

Syriac, like other living languages, has different dialects. Each dialect has its particular character depending on the demography and surrounding circumstances. The map of Syriac dialects does not necessarily synchronise with the various churches of Iraqi Christians. This means that followers of different churches may speak the same dialect, while followers of one church might speak different dialects. However, speaking and understanding among these people is normal and easy because the minor linguistic differences of various dialects only involve pronunciation.

The Iraqi Christians share the same customs and social traditions which reflect their unified identity—Christian principles and values that have been in place since they embraced Christianity in its very early stages in Mesopotamia at the hands of Mar (Saint) Thomas (one of the Twelve Apostles), Mar Addai, and Mar Mary, two of the Seventy Apostles.[4]

Despite the accumulated historical diversity and schisms in their theological views and churches, the Iraqi Christians intermarry between their Christian denominations. And despite the multiple names ascribed to this cultural and ethnic entity in the past, they firmly believe in the unity of their ethnicity, culture, and destiny.

Demographic Distribution Of Iraqi Christians

Based on the historical claim that the Iraqi Assyrian-Chaldean-Syriac Christians are the indigenous people of Iraq, it is notable that their primary residences are the country plains around the historical capital of the Assyrian Empire of Nineveh (now Mosul).

Due to colonialism and the expansion of Islam (Arabs coming from the south and Kurds from the north and northeast), the whole region was eventually controlled by Muslims, forcing Christians to become a religious minority struggling to survive.

Many Christian towns in the region, such as Alqosh, Telkeif, Bartilla, Zakho, and Mangesh, still exist. Historical evidence indicates churches as well as Christian communities had a presence in big cities in Northern Iraq and Iraqi Kurdistan, such as Mosul and Erbil. Christians, however, also exist in other big cities such as Baghdad, Kirkuk and Basra. Their roots go back to earlier Assyrian and Christian communities; social and economic factors caused Christians to move to these cities to seek a better life. The Iraqi Christians have lived in Baghdad and Kirkuk since the times of the Abbasids, Mongolians, and Ottomans.[5]

Other political and security reasons played important roles in encouraging migration to large cities. From the 1960s to the 1980s, migration to the large Iraqi cities, especially Baghdad, has significantly increased because their historical places of habitation and villages in Iraqi Kurdistan, particularly in the regions of Duhok and Erbil, became sites of military battles between the Kurdish revolution and central government troops.

The pace of migration escalated, particularly after the Baath regime took power in Iraq in 1968 and began adopting a policy of burning the land. The policy of destroying the Assyrian and Kurdish villages in the north, lasted from 1974 to 1988 and resulted in the obliteration of 4,000 villages, among them some 120 Assyrian Christian villages and the destruction of more than 60 ancient churches. The regime also practiced ethnic cleansing by deporting thousands of Assyrians and Kurds to other places, replacing them with Arabs in the former Assyrian/Kurdish homes and villages. However, beginning in 1991 with the liberation of the Iraqi Kurdistan region, a significant movement began to return and rebuild the life in the destroyed villages. This movement increased Saddam’s regime fell in 2003.

Therefore, we may describe the Christian demography in Iraq as follows:

I- The geopolitical demography, in terms of population and lands (towns, townships, villages) exists in two regions:

1- Iraqi Kurdistan region: particularly in the governorates of Dohuk and Erbil where around 120 Christian towns, townships and villages exist.

2- Nineveh Plains: where a substantial Christian population exists (to be introduced in detail in the sections that follow).

II- Christians in the big, mixed cities of Baghdad, Basra, Mosul, Kirkuk, and Sulaymaniyah have, has faced real threats, especially in Basra, Baghdad, and Mosul, because of a systematic anti-Christian terror campaign and ongoing religious cleansing in many parts of these cities.

This existence, which has survived over many centuries, might be extinguished if circumstances are not changed.

Iraqi Christian Demography

The current Iraqi administrative structure is composed of 18 governorates (or provinces), each composed of districts (the governorate centre is also always a district centre) which, in turn, are composed of a couple of sub-districts, to which the townships and villages belong.

The difference between the two aforementioned demographic types (i.e. in the Kurdish Region of Iraq and the Nineveh Plains, and other parts of Iraq) is that in both the Kurdish Region of Iraq (KRI) and the Nineveh Plains, people have a historical connection to the land.

This enables Christians to preserve, practice, and improve their collective identity and to have a political and administrative role in the planning and decision-making of these territories. In addition, social and cultural entities/services can operate and add value to the community. Whereas, in other parts of Iraq, Christians only represent a tiny part of the roughly seven million population of Baghdad or several thousand scattered amongst the millions of Basra, Mosul and Kirkuk.

The Christian presence in KRI has some important differences with the Nineveh Plains. The existence in KRI is mostly in rural villages (over 100) and in the big cities like Duhok, Ankawa (the sub-district in Erbil), Zakho and others; most of those villages are not mixed, i.e. all their people are Christian, while only a couple of them are mixed with Yazidis and/or Muslims, such as Sorka, Sorya, and others.

The size of the villages ranges from the small (up to 15 families) to the large (less than 100 families) and even to the largest of them, where the quantity reaches 250 families. The Christian villages in KRI are very exceptional in the region’s history.

The Christians have never returned to the villages and regions from which they were forced to flee, e.g. Hakari, Tur Abdin (in modern Turkey), Urmia (in North Iran) and in Khabour (Syria). Only in Iraqi Kurdistan have the deported Christians gone back to their home villages and rebuilt their lives.

The Christians in the Nineveh Plains mainly exist in semi-large populated townships and towns. In many cases, Christian towns in the Nineveh Plains are district centres (e.g. Hamdaniya) or sub-districts (Bartilla, Alqosh).

There are no Christian towns or villages in Iraq south of the Nineveh Plains to the Saudi and Kuwaiti borders, nor to the eastern and western Iraqi borders. This illustrates important current and future concerns of Iraqi Christians amid geopolitical circumstances. It also poses new questions on the structure and future of Iraq and neighbouring countries.

Another important factor in considering the region’s long-term borders is that the Christian Assyrian demography in KRI and Nineveh Plains has the same demography in Northeast Syria and Southeast Turkey (Tur Abdin), similar to the Kurdish demography in KRI which continues the Kurdish demography in Iran, Turkey and Syria.

Figures for Christian Demography in Iraq[6]

| Year | Iraqi population | Muslims | Christians | Jews | Yazidis | Mandeans |

| 1947 | 4,562,000 | 4,256,000

= 93.34% |

149,000

= 3.27% |

117,000

= 2.56% |

40,000

= 0.88% |

|

| 1957 | 6,339,960 | 6,057,493

= 95.54% |

206,206

= 3.25% |

4,906

= 0. 07% |

55,885

= 0.88% |

11,825

= 0.18% |

| 1977 | 11,862,620 | 11,474,293

= 96.7% |

253,478

= 2.14% |

381

= 0.003% |

102,191

= 0.86% |

15,937

= 0.14% |

The Census of 1977

Iraq, like all other Arab and Islamic states with many ethnic and religious minorities, lacks transparency regarding statistics and figures of minorities and their political, religious, social and cultural conditions. However, with the fall of the Saddam regime, many secret documents, statistics and reports were released and became available for researchers.

The Political Department in the General Security Directorate, the former regime’s high office concerned with Iraqi religious minorities, noted in the Iraqi census of 1977: The results of the latest census of 1977 show Muslims in Iraq are the majority of the population. Their number is 11,474,293 persons; this is around 97% of the overall Iraqi population, which is 11,862,620. Therefore, the other four religious groups (Christians, Yazidis, Mandeans, and Jews) are religious minorities in Iraq. Their numbers are as follows: (Christians) 253,478 i.e., 2.14% of the Iraqi population; (Yazidis) 102,191 i.e., 0.86%, (Mandeans) 15, 937 i.e., 0.14% and (Jews) 381 i.e., 0.01%.

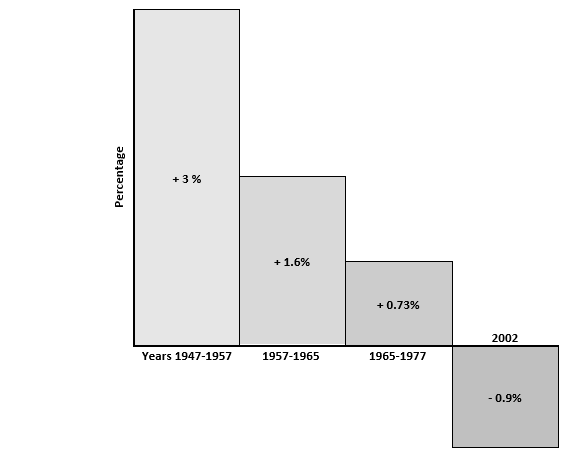

However, the study’s most dangerous indicator is the continuous decrease in the annual population growth of Iraqi Christians. The paragraph titled ‘Population growth indicators between religious groups in Iraq 1947–1977’ notes:

The population growth average between Christians was very close to that of Muslims for the period 1947–1957. The average was more than 3% per year. We notice the rapid decrease in growth to 1.6% between 1957 and 1965. Despite the fact that this is a very small average, it continued to decrease rapidly to reach 0.73% per year between 1965 and 1977. This is a very low average and is close to the population growth average in developed countries.

According to Operation World in the United Kingdom, the Christian population’s annual growth in Iraq in 2002 was negative: -0.9%!

Iraqi Christian Population Annual Growth

Administrative and Geographic Origin of Nineveh Plains

The term ‘Nineveh Plains’ had never been used in administrative or geographical contexts the way it is used now in the Iraqi official documentation or administrative structures. After the Saddam regime was toppled in 2003, ‘Nineveh Plains’ emerged in the Iraqi political and media discussions and hence by the international media.

The term was created and developed because the plains became a sanctuary for Christians fleeing violence and organised terrorism which targeted them in the cities under Iraqi central government jurisdiction, such as Mosul, Baghdad, Basra, Anbar, and other areas in which Christians existed. In contrast, the Peshmerga forces and Asayesh security forces who receive their orders from Kurdistan region, had created on the Nineveh Plains, a stable atmosphere, except for some rare security breaches. Also, the Nineveh Plains had a historical Christian presence; for many IDPs, it had been their homeland before they migrated to bigger cities to seek better education and employment opportunities. Therefore, most IDPs in the Nineveh Plains after 2003 had simply returned to where they originally came from. The same applied to Yazidis— particularly those who living in Mosul and who sought security in the Yazidi towns and villages in the Nineveh Plains. Having the Plains transformed into a haven for Christians and Yazidis transformed the ‘Nineveh Plains’ into a term indicating an administrative area secured for minorities.

Despite the near universal acceptance of the term ‘Nineveh Plains’ and its constitutive administrative units—including Telkeif, Hamdaniya, Sheikhan districts along with their sub-districts and villages, and the Baashiqa sub-district that is under the jurisdiction of the central district of Mosul (Mosul city, the capital of the Nineveh governorate)—the geography and its administrative formation has been debated since 1991 because of changes in administration and security control over it, or some parts of it.

Nineveh Plains administrative composition[7]:

- District of Telkeif, whose centre (capital) is the city of Telkeif, has two sub-districts, Alqosh, Fayda and Wana, and many villages.

- District of Hamdaniya, whose centre is the city of Baghdeda (Qaraqosh or Hamdaniya), has two sub-districts, Bartilla and Nimrod, and many villages.

- District of Sheikhan, whose centre is the city of Ain-Safni (Sheikhan), has the sub-districts Zelkan, Qasrok, Baadrah and Kalakji.

- Sub-district of Baashiqa, which is under the district of Mosul city centre.

The cultural, religious and ethnic composition[8]:

Nineveh Plains, considered Iraq’s most religiously, nationally, and culturally diverse area, contrasts with other, homogenous Iraqi cities. The Nineveh Plains contains Muslims, Christians, Yazidis and Kaka’aies, the latter of whom, despite being registered in the Iraqi identity directorate as Muslims, maintain their unique religious identity. Denominationally, the Nineveh Plains contains Sunni and Shia Muslims, as well as Catholic, Orthodox and Church of the East Christians. Arabs, Kurds, Chaldeans, Syriacs, and Assyrians live in the plains (the term ‘Suryaye’ is widely used to refer to Chaldeans, Syriacs, and Assyrians). The Shabaks, considered one of the mains ethnic/cultural groups of the Nineveh Plains, are mostly Shia Muslims with some Sunni Muslims, yet they dispute their national identity; some consider themselves to be Kurds, while others identify as Arabs. The third fraction presents themselves as being just Shabaks. The Arabic, Kurdish and Syriac languages are spoken on the Nineveh Plains, in addition to the language of the Shabak.

Economic Resources

The ‘Nineveh Plains’ includes the area’s basic economic resources of agriculture and animal husbandry, in addition to some food industries. Along with widespread cultivation of wheat and barley, Baghdeda (Qaraqosh) has the basic production of poultry and calves for Nineveh and neighbouring governorates. Baashiqa and its surroundings produce olive oil, Tahini, pickles and related products.

Given the area’s proximity to Mosul, the economic resources also include jobs related to small-scale industries as well as factories producing decorative stones. The Nineveh Plains is located between two mains roads, one of which connects Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city, and Erbil, the KRG capital. The second main road connects Mosul with Turkey through Duhok—hence the areas close to the borders of Mosul have now become important economic centres.

Religious Tourism[9]:

Despite the lack of infrastructure and weak support from the relevant federal and local governments, the Nineveh Plains have played a big role in religious tourism, with the potential to grow exponentially, since it includes many shrines and religious sites of all different religions.

The Plains’ many important Christian monasteries include:

- Hurmezd monastery in Alqosh, which is now run by the Chaldean Church (it was historically established and developed as one of the Church of the East’s monasteries).

- Matthew monastery in Mount Maqloub, which is one of the most ancient monasteries of the Orthodox Church.

- Behnam Monastery in Namroud, which is the one and only monastery that belongs to the Syriac Catholic Church in Iraq.

Important religious shrines include the Prophet Nahum Shrine in Alqosh, which was formerly a synagogue and remains an important site for Jews. It is believed to be where the prophet Nahum is buried. Furthermore, the most sacred shrine in Yazidism, the Shrine of Sheikh Aadi in Lalish Valley, is located in the Nineveh Plains, in addition to other shrines in Yazidis towns also in the plains. For Shi’ite Muslims, the shrine of Imam Ridha, who was one of the twelve imams of Shi’ism, is located in the Nineveh Plains.

In addition to these religious sites, the Nineveh Plains has many archaeological sites such as Mesopotamia, Dour Sharokeen, and Nimrud (which are two Assyrian capitals), as well as being the location of Khanas, where the winged bulls (‘Lamassus’) were produced and shipped to Mosul via the Khousar river.

Let´s have a closer look to the Christian Demography in Nineveh Plain and its Administrative Geography.[10]

The Christian presence in the Nineveh Plains owes its strength to its historical roots, which go back to pre-Christian times, since the plains surrounds the city of Nineveh (modern-day Mosul)—one of the most important capitals of the Assyrian Empire—as well as Dour Sharoukeen (modern-day Khorsobad), which was also one of the ancient Assyrian capitals. The Christian presence, therefore, is the most important demographic continuation for the Assyrian national existence.

A further strength of the Christian demography in Nineveh Plains is that they make up most of the key town and administrative centres that form the Nineveh Plains. Christians make up around 95% of Baghdeda (Qaraqosh, Capital of Hamdaniya district) and used to be the majority in Telkeif District just before the mass Chaldean migration to the United States of America because of an Arabisation policy; the city now has a majority of Sunni Arabs.

This also applies to the purely Christian city of Alqosh. The city of Bartilla once had a majority Christian population before the organised demographic change of the early 1980s. Now the surrounding Shabaks have increasing political and economic capabilities. The Christians in Baashiqa make up around 25% of the population with the Yazidis as the majority with 60%. The Christian demography in the Nineveh Plains suffers a key weakness of semi-detachment from neighbouring Christians with no connection on the ground among one another, in contrast to the Yazidis and Shabaks.

Christian Churches Diversity

The Nineveh Plains has a diversity of traditional Christian apostolic churches, except the Armenian Church. These include the Syriac Orthodox church, Syriac Catholic Church, Chaldean Catholic church, Assyrian Church of the East, and Ancient Church of the East. The density of these churches varies as they have different locations in the Plains’ geography.

For instance: the Syriac Catholic Church, which some consider to be the largest church of the plains, is within the city of Baghdeda (Qaraqosh) while the Syriac Orthodox church has its followers in Bartilla, Baashiqa, Bahzani, Baghdeda, and the villages of Mergi, Lfaf and Maghara on the foot of Mount Maqlob and which are in the St. Matthew diocese.

However, the Chaldean church, which others claim as the largest church in the plains, is situated in the northern parts of the Nineveh Plains, in the cities of Telkeif, Alqosh through Batnaya, Baqofa, Telsquf, and in Jambour, Bandawaye, Sheikhan, Karmles (south of the plain). While the Assyrian Church of the East is present in small villages near Alqosh such as Sharafiya, or on the road connecting Alqosh to Sheikhan such as Ein Baqri, Dashqotan, Karanjo, Perozawa, Garmawa and Sheikhan; the inhabitants of these villages have roots from Hakari Assyrians (south of Turkey) who fled their country to Iraq during the Ottoman Genocide in WW1 against the Christians of the Ottoman Empire: Armenians, Assyrians Syriacs, and Greek. The Assyrians of Rekan area of Heesh, Estip and Maydan villages in Duhok governorate settled in Telkeif in the mid-1970s after being deported by the former Baath regime.[11]

The importance of the Nineveh Plains for Christians

The Nineveh Plains is important the Christians of Iraq for many reasons. The foremost include:

- It represents their deeply-rooted national and cultural identity going back to the centuries before Christ. They are the heirs of the Assyrians of the Assyrian empire whose mains capital was Nineveh (current Mosul). The plains encompasse other Assyrian capitals and cities such as Nimrud, Khorsabad, Khans, and others.

- With the great and continuous decline of Christian demography in Iraq, the Nineveh Plains is one of only two concentrated areas of Christians. (The other area is the governorate of Duhok in the Kurdistan region and some areas of Erbil, specifically Ankawa.) This important demographic presence in the Nineveh Plains has an additional important power component inextricably linked with Christian demography in Duhok governorate. This makes them vital, especially if the Nineveh Plains joins the Kurdistan region in the near or medium term, because this makes interaction between the Nineveh Plains and Duhok vital and influential in the long-term strategy of connecting with the presence of Assyrian Syriac Christians in northeast Syria and southeast Turkey (Tur Abdin).

- The Christian community in the Nineveh Plains has the economic resources of the vast land and the agricultural, industrial, and commercial establishments that have grown and developed cumulatively and have not been affected by the political unrest and conflict in Iraq (pre-ISIS). The Nineveh Plains, unlike the Christian villages and towns of Duhok, has not been subjected to displacement and destruction, which created an atmosphere of local stability sufficient for developing these resources.

- The Nineveh Plains, like the whole Christian presence, has many economic and academic capabilities. This makes investment in these resources for economic development in the Nineveh Plains possible and also makes them, especially in the parts of the plains that includes Yazidis and Christians (from Alqosh and Telsquf to Baashiqa and Bahzani), an environment suitable for economic activities that cannot be achieved in the rest of Iraqi denominated by Islamic environment, especially the Sunni and Shia Arabs.

- The Nineveh Plains, unlike all other Iraqi regions (except for the city of Kirkuk), is characterised by a diversity of religious, ethnic and cultural minorities without a specific identity holding a majority. This allows all its minority components, including Christians, to play a greater role in political, administrative, economic, and community activities in the plains. It is the right environment for Christians to play their role as a bridge between these different minorities.

- The Christian presence in the Nineveh Plains is characterised by its concentration and heavy weight in the centres of the administrative units, which enabled the Christians to assume important administrative positions in the administrative units of the Nineveh Plains (the mayor of Telkeif, Hamdaniyah districts, and mayor of Alqosh sub-district).

Nineveh Plains under Ba’ath regime

After the Ba’ath regime seized power by a military coup in June 1968, to some extent, it formed a secular regime with Arabian fascist policies imposed on non-Arab people such as the Kurds, Assyrians, and Turkmen. It later shifted to add an Islamic dimension to its rhetoric, practices, and policies, especially while the Iraqi-Iran war was still waging, then followed by the First Gulf War (Battle for Kuwait) led by the USA, and then the long economic siege imposed on Iraq.

The Nineveh Plains, the only area of Iraq without Muslims and Arabs as the majority of its inhabitants, became a target of the regime’s Arabianisation and Islamisation policies. Since the 1970s, in parallel with forcibly displacing the Kurds and Assyrians from Iraqi Kurdistan followed by the collapse of the Kurdistan revolution in 1975 with the signing of the Algerian treaty and the Arabisation of large swaths of the Kurdish region (for example, the Slevani area in Duhok governorate), the regime adopted the policy of Arabising the Nineveh Plains and particularly its Christian territory. This policy expanded during the Iraqi-Iranian war by laws granting properties to Arab civil servants and military personnel in the Christian plains of Nineveh in Telkeif, Baghdeda (Qaraqosh), Bartilla, and other areas. Furthermore, these practices were followed by Islamising policies of building mosques in these areas and villages despite the light presence of Muslim families there. However, the regime intentionally neglected providing health, economy and education services to the the Nineveh Plains leaving it dependent on services provided in Mosul and hence under the Islamic Arabian influence. Also, the regime had tightened its grip on Nineveh Plains through its security agents despite the plains never any sort of demonstrations or opposition to the regime’s policy even when the Iraqi revolution broke out in the aftermath of Kuwait war. Many Christian young people from the Nineveh Plains escaped the compulsory military service during the Iraqi-Iranian war by fleeing to Iranian territory through Kurdistan and then seeking asylum in the west. The same applied to many Christian families who fled their villages in the Nineveh Plains after the end of the Iraqi-Iranian war and as a result of the international sanctions imposed on Iraq; they sought asylum in neighbouring countries and then in the west.[12]

Pre-ISIS Nineveh Plains 2003-2014

The collapse of the Saddam regime in April 2003 was not just a regime change like other coups that took place in the Middle East and elsewhere. Saddam’s totalitarian regime had held an iron grip on individuals and families of Iraqi community, and hence on all of the Iraqi state institutions; this resulted in the state itself collapsing, not just the regime. As a consequence, Iraq after 2003 was transformed into a territory of political parties with their loyal militias that imposed their own rule of law in particular areas.

The weak and scattered minorities without influential political and military establishments and the wealth of the Christians and Mandeans made them an easy, attractive target in the mid-south Iraq area by jihadist Sunni and Shia militias, as well as by organised crime gangs. The Shlomo Documentation Organization stated that 1,174 Christians including 14 clergymen have been killed between 2003 and 2014 (pre-ISIS) in territories under the Iraqi central government. In the terrorist assault on The Lady of Survival Church in Baghdad on 31 October 2010, 53 Christians were martyred while attending church service. There were 114 attacks on churches in Baghdad, Mosul, Kirkuk, Anbar, some of which have been targeted more than once. Christians were also kidnapped for ransom. [13]

All of these systematic assaults based on religious identity left the Christians with no choice but to flee to safer areas on the Nineveh Plains and Kurdistan region, or apply for resettlement visas to western countries. Some cities, such as Ramadi, Khalidiya and Habaniya, no longer have any Christians, whereas their presence has considerably decreased in the key cities of Baghdad, Basra and Mosul. Baghdad had an estimated 250,000 Christians before 2003, this number has decreased to approximately 40,000. Around 16 churches have been shut down in Baghdad. Therefore, Christians fled to Nineveh Plains as a safe territory for the following reasons:

- The stable security situation in the area which had been under the command of Peshmerga forces and Kurdistan Asayesh (security personnel).

- Almost all of the Christians had family roots in the Nineveh Plains, but left it years ago to seek better financial conditions in larger cities.

- The plains had a generally Christian-embracing atmosphere.

- The Arabic language taught in schools and spoken at official directorates and local markets made it easier for them to integrate. Whereas in Kurdistan, they would face difficulty with a Kurdish language they had never studied or spoken.

From the early days after April 2003, there had been multiple displacement waves to Nineveh Plain; for instance, in 2004, 2006, and 2010. The Yazidi community, like the Christians, also fled the larger cities, especially Mosul city in which no Yazidi person remained when ISIS took control. They went to Nineveh Plains and the Yazidi community complexes. This massive displacement to the plains created a huge pressure on the economic market as well as the infrastructure.

The table below from a survey conducted by Christian Aid Program – Nohadra – Iraq CAPNI, is a sample of the number and percentage of displaced Christian families who fled Iraqi cities to the Christian towns and villages in Nineveh Plains (The figures are from October 2006):

| Place | Residing families before exodus | Displaced families due to exodus |

| Telkeif | 1000 | 400 |

| Batnaya | 650 | 400 |

| Baqofa | 116 | 40 |

| Tellsquf | 1100 | 400 |

| Sharafiya | 90 | 21 |

| Alqosh | 1700 | 520 |

| Bartilla | 2250 | 750 |

| Qaraqosh | 5000 | 1050 |

| Karmles | 600 | 180 |

| Place | Residing families before exodus | Displaced families due to exodus |

| Ein Baqre | 35 | 6 |

| Karanjo | 35 | 8 |

| Dashqotan | 20 | 0 |

| Pirizawa | 30 | 10 |

| Garmawa | 5 | 1 |

| Sheikhan | 200 | 150 |

| Baashiqa | 750 | 315 |

| Bahzany | 155 | 50 |

| Total | 13736 | 4301 |

So, for every three families the fourth is a displaced one!!!

The percentage is even more than in the governorate of Dohuk.

Some people incorrectly assumed that ISIS appeared, expanded, and controlled two-thirds of Iraqi territory including Nineveh Plains in summer 2014 as the result of ‘cross-border terrorism’ (as described by an Iraqi diplomat at a conference in the United Nation’s sub-HQ on February 2018 in Vienna, Austria). However, ISIS had been present and growing with its jihadist ideology in the Sunni Arab community of Mosul city and surrounding territory. It resulted from the inflammatory rhetoric of the Baath regime’s ‘Faith Campaign’ in 1996 that depicted the sanctions and its health and economic consequences on Iraqi living conditions as part of a western ‘crusade’ against Islamic countries.[14]

Mosul city and the governorate of Nineveh have been an Arab Sunni stronghold with deeply political Islamic roots. Because of its Arabic ideology and its well-known stances against non-Arab components of Kurds and Assyrians, it formed, alongside the governorate of Anbar, a fertile environment for Sunni Jihadist organisations. The ISIS was publicly present in Mosul city for years until they controlled it completely and imposed their Sharia (laws) on the Mosul community and everyday life including the Christians.

Churches used to regularly pay money to the jihadi organisations in return for their own safety. These organisations pressured Christians to not show crosses or ring church bells. Christians also had to pay to protect their supermarkets and economic projects. The religious rhetoric along with education became jihadist rhetoric. The lifestyle, culture, and social environment in Mosul all came under the grip of Islamic Sharia.

These factors, along with the absence of the rule of law, created space to target the Christians, their churches, and their properties. More clergy were martyred in Mosul than all other Iraqi cities combined. These terrorist acts forced the Christians of Mosul to leave the city seeking security. Nineveh Plains was one of these areas where Christians from Mosul and the rest of Iraq headed to, something that created service and economic pressure on the host community in the plains.

The tense atmosphere of Mosul resulted in the Nineveh Plains communities fearing to connect with or seek services in Mosul and seeking alternatives. For example, the targeting of university buses that had been transporting students from Nineveh Plains to Mosul University on 2 May 2010 was perceived as an explicit threat. The jihadist ideology expanded to the Sunni Arabian community in Nineveh Plain; this could be explicitly witnessed through religious rhetoric on mosque podiums as well the lifestyle atmosphere. Once ISIS controlled Telkeif, many in the Sunni Arab community joined the insurgents and looted Christian, Yazidi, and Shia properties.

Nineveh Plains under ISIS

When ISIS gained control over the city of Mosul in June 2014, the Nineveh Plains, along with the governorates of Iraqi Kurdistan, turned into a safe haven for Mosul Christians and other non-Muslim, and non-Sunni communities fleeing from ISIS. Most observers and analysts believed that ISIS would, after Mosul, go to Baghdad through the governorates and Sunni territories.

However, for reasons that are still unclear, on 3 August, ISIS advanced to the Yazidi-dominated Sinjar region where it committed the terrible crimes of genocide, sexual slavery, and kidnapping, as well as destroying public and private properties. Sinjar was a warning for the Nineveh Plains, to which ISIS headed on 6 August, and so the Nineveh Plains gained a three-day advantage in which its inhabitants were able to escape to the governorates of Duhok and Erbil. When ISIS moved towards Erbil, the coalition air force intervened and stopped their advance so that the front lines were between the Peshmerga and ISIS. The lines remained unchanged until the retaking of the Nineveh Plains in the summer of 2016.

It is a painful coincidence that on the night of August 6, 81 years ago (1933), the Semile massacre began against the Christian Assyrians and its memory remains stuck in the collective memory of the people, and the wound is renewed again on 6 August 2014.

Thus, the Nineveh Plains, for the first time in its history, was completely emptied from its Christians, Yazidis, Shia Shabaks and, and groups of Sunnis Shabaks. Most Arabs and Sunni Shabaks in Telkeif, Salamiya, Nimrod and Fadhiliya regions remained coexisting under and with ISIS. When front lines became stable, people returned to cities, towns, and villages such as Alqosh, Khatara, Jambur, Busan, Telsquf which had been abandoned out of fear of ISIS. In August 2014, Telsquf remained ten days under ISIS until it was liberated by the Peshmerga.

The occupation of the Nineveh Plains caused tremendous damage to personal and public properties, in addition to religious and archaeological sites and buildings, as well as infrastructure, shops, agricultural and industrial facilities, and others. The short and long-term effects of ISIS control of the Nineveh Plains have gone beyond the enormous physical and economic destruction that requires decades to rehabilitate. Physical destruction has moral and psychological effects and harms individual and collective human dignity. It also affected the links between the community components, especially among Christians and Yazidis, on the one hand, and Muslims, specifically the Sunnis, on the other. Restoring these damaged links, among other things, are the challenges of return to the Nineveh Plains after ISIS.

Post-ISIS Nineveh Plains 2016: Regaining Control on Nineveh Plain

I personally hesitate to use the term ‘liberation’ from ISIS for this term contains many meanings which remains incomplete. I would use the term ‘retaking’; it refers to the reality on the ground. What has been achieved is no more than regaining security, military, and administrative control over the areas once under ISIS.

The Kurdistan Peshmerga forces had been on the thousand-kilometre frontline with ISIS stretched from the Syrian border in northwest to Diyala in the mid-east of Iraq. Therefore, retaking control over areas under ISIS from Sinjar to Kirkuk through Nineveh Plains should have been launched from Kurdistan territory, and Peshmerga forces should have participated in military operations. Despite the political conflict between Baghdad and Erbil along with their future ambitions some sort of agreement between Baghdad and Erbil concerning territory control after the retaking phase was necessary. This sort of agreement, some believed to have been American-sponsored, allowed the relaunching of military operations to defeat ISIS and regain control over the areas they once held.[15]

In Nineveh Plains, the Peshmerga forces would retake south of Mosul Dam then west to the south of Batnaya, Baashiqa to further west of Hamdaniya, while the Iraqi Army on the other side along with the Public Mobilisations Units (Alhashid) would retake the rest of the areas along with Mosul city till the Syrian border. Hence, the security and military control over Nineveh Plains shifted from being purely under Peshmerga and Asayesh control before ISIS to an area divided administratively between KRI and Iraqi federal government.

With the retaking of Nineveh Plains, the villages of Baqofa, Telsquf up to Alqosh, Baashiqa, and Bahzani up to St. Matthew were under Peshmerga jurisdiction. Whereas Telkeif, Bartilla, Karmless and Baghdeda (Qaraqosh) became under the control of the Iraqi Army and the Public Mobilisation Units (Alhashid). The Christians in Nineveh Plains had greatly feared this scattering and tearing apart between two security administrations and two constitutional administrations.

Taking back the Nineveh Plain, especially the east bank of Mosul city, revealed the enormous destruction resulting from ISIS control over these areas and resulting military operations. The people of the Nineveh Plains have been under great shock of the devastation to their own properties such as houses, trade businesses, and farmland. Also damaged were the infrastructure and service units of schools, health centres, water networks, electricity, and official directorates. The ISIS even intentionally demolished the churches and religious institutions of Christians, Yazidis, and Shia.

Nineveh Plains After Kurdistan referendum

In the summer of 2017, after regaining control of the ISIS military zones, the Iraqi political scene and KRI faced a new challenge of the Kurdistan Democratic Party KDP to call for a referendum on the right to self-determination and independence of Kurdistan from Iraq. The demand for self-determination is not new to Kurdish political parties. However, in Kurdistan, this demand cannot be isolated from its consequences on regional and international stability. Hence, the call for the referendum was unanimously rejected by all countries from the neighbouring countries, influential Middle Eastern countries and European and North American powers.

From the point of view of Christians, the referendum held in the Nineveh Plains reflected the big question about the administrative subordination between Iraqi federal government and KRI. The call for the referendum and its aftermath, followed by the expansion of the Iraqi army and the militias of the Popular Mobilisation and the decline of the Peshmerga caused confusion. Displaced people were less inclined to return to their homes in the Nineveh Plains. People identifying as Christian had been divided between the military and security administration of KRG (Baqofah, Telsquf, and the rest of the northern Nineveh Plains and the villages of Jabal Maqloub), and the region of the military and security administration of the central government administrative (Telkeif, Batnaya, Bahzani, Bartilla, Qaraqosh and Karmless).

The open question remains about reunifying the Nineveh Plains and restoring the natural, living, economic and social interaction between its regions. The complex and subjective answer is not limited to the wishes of the people of the plains, but includes interests and aspirations of Iraqi Shia, Kurdish and Sunni decisionmakers and the neighbouring countries. The Shia led by Iran and Sunni led by Saudi Arabia have turned Iraq and Syria into a conflicted arena that does not place a high priority on the interests of vulnerable minorities.

The de facto stability of Nineveh Plains encouraged more families to return home. Local and international humanitarian organisations, including United Nations organisations, helped fill the vacuum caused by the almost complete absence of the Iraqi government in reconstruction programs. (Appendix 5)

All returnees to the Plains faced significant challenges. The first and most basic challenge facing the displaced is the harm and destruction, partial or total, of their homes (see table in Appendix 4) and the looting and pillaging of all their household possessions. Families cannot deal with this challenge because their limited resources had already been exhausted during their displacement. International organisations could only partially rehabilitate the destroyed houses.[16]

The most important challenges are

Plurality of security and military forces[17]: The Peshmerga and Asayish forces in the Nineveh Plains areas under the control of KRG that offers a feeling of individual and collective safety, the Iraqi central government does not. For example, the military and security administration of the Christian- dominated areas under the control of the central government are shared with three politically affiliated militias: The Babylonian militia in Telkeif and Batnaya, the Shabaki popular mobilisation militia (Brigade 30) in Bartilla, Baashiqa, and Bahzani, and the Nineveh Plains Units in Qaraqosh and Karmless. The militias never provided stability and security for the people, and this is not expected in the Nineveh Plains.

Administrative Structure and Reference: Although the central government has officially recognised the administrative unit of the Nineveh Plains, many administrative units exist on the ground. For example, Sheikhan district, officially linked to the governorate of the Nineveh, and Alqosh sub-district, officially under Telkeif, both are practically under the authority of KRG. This duplication may not have much impact on the daily life of the Nineveh Plains people, where its impact is limited to several government departments and documents, but it is an effective challenge in any political process related to the normalisation of administrative and security conditions for the Nineveh Plains, or the application of the Iraqi Constitutional Article 140.

Political Intersections: All Iraqi political parties, with limited exceptions, have religious or sectarian affiliations. One reason might be the weak identification with the Iraqi state. The constitutional, legislative and administrative restructuring and political instability of post-2003 Iraq led to political forces using violence to achieve their demands. The plethora of political organisations active on the Nineveh Plains reflects its ethnic, religious, and sectarian diversity. These organisations seek to expand their popular base in various ways, including the misuse of security and administrative services. This puts additional strains on the daily lives of people of the area and threatens any practical programs to restore trust and peaceful coexistence among the communities.

Economic Challenges: The economic challenges of returning to the Nineveh Plains are not limited to the enormous destruction from ISIS or the accompanying military operations to regain control. Considerable medium- and long-term funding must transcend the complicated political, security and administrative situation in order to rehabilitate economic activity that ranges from small workshops to medium-sized activities (industrial and agricultural production plants) and large-scale livestock enterprises, e.g., area of Qaraqosh. This challenge is compounded by the total absence of the Iraqi state and the lack of financial resources. Funds are limited to the contributions of the already affected citizens and the humanitarian organisations operating in the region, whose limited resources cannot cover the needs.

Public-Service Challenges: the Iraqi state neglected for many decades the infrastructure and basic services on the Nineveh Plains. This neglect increased after 2003, especially with the conflict between the federal government in Baghdad and KRG. During the ISIS occupation, the deterioration of these structures and destruction increased. This has resulted in a lack of quantitative and qualitative minimum in basic sectors such as health, education, electricity, water, sanitation, and roads, which increases the burden of life for returnees.

This context shapes the challenges of rehabilitating places of worship, church-operated institutions, and service centres that include kindergartens, youth centres, welfare centres, sports and social centres. Rehabilitating worship places materially helps maintain identity and a sense of identity. Thus, the houses of worship are important in the process of return and stability. They send a message of future reassurance, which the central government has failed to do. This reconstruction has been left to the targeted communities with limited resources or international humanitarian organisations, which usually do not rehabilitate places of worship.

Challenges of Community Coexistence: Since the establishment of the modern Iraqi state, it has not had the strong cohesion that preserves society from dissonance and conflict between its components. During most stages of the history of contemporary Iraq, the state, its political system, and its military and security tools were part of this conflict; for example, the bloody conflict with Kurds and Shias.

The rapid expansion of ISIS control over nearly two-thirds of Iraq demonstrates the lack of community cohesion. The politicians of Iraq, as well as the people of the communities targeted by ISIS, did not know that many Sunni Arabs had aligned with the ISIS and joined and participated in the terrorist operations against components of their community that shared daily life in the cities and areas controlled by ISIS.

This makes it impossible in some places and difficult in other places to expect community peaceful coexistence based on trust and mutual respect. People remember bloody, painful events in their lives. The government does not have any real program to deal with this memory and offer victims of ISIS victims their legal, moral, and material rights such as transitional justice and accountability of those involved in crimes of ISIS. It does not compensate the victims and reassure victims that what happened will not be repeated again.

The official and institutional Iraq still has not dealt with what happened as an existential threat to the social structure. So far, no national debate has been held about what happened. Why did it happen? How did it happen? How could its recurrence be prevented?

The constitution, Iraqi legislation, curricula of education, and political and religious discourse have not changed nor addressed the causes of the disaster. Hence, it is almost impossible for non-Muslim minorities victimised by ISIS to trust returning to predominantly Arab Sunni areas. For example, Christians and Yazidis find it almost too difficult to return to the city of Mosul or the city of Telkeif.

Peaceful coexistence among the communities of the Nineveh Plains is a big and growing challenge, especially with the recruitment of religious and sectarian political parties and their affiliated and influential militias in the Nineveh Plains. These political parties and militias existed even before ISIS with activities in the areas of Bartilla and Hamdaniyah by the Shia Shabak, and in Telkeif by the Sunni Arabs[18].

Post ISIS Challenges in the Nineveh Plains

While these challenges affect all ethnic, religious and sectarian components in Nineveh Plains, the impact on the Christian community in the post-ISIS period relates to future Christian demography, which is threatened in many cities and areas of the Nineveh Plains.

Several factors affect Christian demography:

- The Christian population in the Nineveh Plains has been dispersed into isolated, unconnected islands and cities. Only some villages surrounding Alqos, and two villages near Telsquf and Batnaya are connected. The six Christian-majority cities in the Nineveh Plains are: Batnaya, Telsquf, Alqosh, Bartilla, Qaraqosh and Karmless). The other four Christian-inhabited cities are: Telkeif (majority Arabs), Sheikhan (majority Yazidis and Kurds), Baashiqa and Bahzani (65% Yazidis). The unknown number of Christian villages in Nineveh Plains are distributed according to administrative units as:

Telkeif: The centre (mixed with Arab majority now) and Batnaya.

Alqosh area: The area centre, Baqofah, Telsquf, Sharafiya, Bandwaye, Ein Baqre, Deshkotan, and Karango.

Sheikhan district: The centre (a small Christian population), Perozawa, and Garmawah.

Baashiqa district: The city centre and Bahzani (25%), the villages of Al-Faf. Mergy and Maghara.

Bartilla district: The Christian city centre (the percentage decreased from almost 100% in 1960s to 40% at present with Shabaks in the majority).

Al-Hamdaniya district: The city centre and Karmless.

This Christian demography is unlike the Yezidi, Shabaks, and Arabs, who are all located in urban and contiguous rural areas.

- Schemes of continuous demographic change began with the former regime and continued after 2003. In Telkeif, this was done by Sunni Arabs supported by Sunni political forces and with Gulf States funding. The Shia Shabaks supported by Shia parties and by Iranian funding also became demographic weapons. This has recently increased, post- ISIS, especially by the Shia Shabaks, with the political support of the central government and the military and security influence of Shia militias.

The weakness and fragmentation of Christian demography, on the one hand, and the weakness and fragmentation of effort and the political influence of Christian parties, on the other, means the Christians have a very weak and futile ability to face these demographic changes. In addition, the central government imposes difficulties and obstacles for obtaining documents such as identity papers. Citizens must visit the relevant departments in the centre of the city of Mosul. This is also the case when returning to official government work or to study at the university in Mosul. Many avoid this, which leads to not returning to Mosul or the Nineveh Plains but rather staying and integrating in the areas of displacement in the Kurdistan region or immigration.

- In parallel with the Christian demographic dispersion in the Nineveh Plains, Christians have a political dispersion and disagreement, albeit in a much more extreme manner, over the political vision of the Plains’ future, its administrative structure and its dependence between the centre and the Kurdistan region.

This lack of agreement results from the delayed start of explicitly ethnic political activity of the Christians of the Nineveh Plains. Historically, and even today, they submitted to the influence of the non-Christians powerful parties or the majority parties. Furthermore, because the Nineveh Plains is a field of conflict between the federal government and KRI, the Christians’ vision of the plains was/is divided between the influence of the centre (both Sunni and Shia) and KRG.

The Christian political forces could not even agree upon the demand to create a Nineveh Plains Province. The two members of Assyrian Democratic Movement, one of the largest Christian parties in the Iraqi parliament, voted on 26 September 2016 in favour of a decision not to change the administrative boundaries of the Nineveh governorate. Also, the Assyrian Chaldean political parties and Assyrian Democratic Movement did not agree to include the Nineveh Plains in the territories subjected to Article 140 of the Iraqi Constitution. This political dispersion and the lack of a unified vision has caused the Christian political and ecclesiastical authorities of the Nineveh Plains to miss the opportunity to have influential political forces in Iraq or the international community to support their causes.

Attractive international opportunities encourage continued migration from home. The large diaspora of Iraqi Christians offers more potential than the homeland, making it a magnet for those who remain in Iraq. This weakens the Christian presence and reduces the potential of the Christian community in the Nineveh Plains to face challenges; it becomes easier to escape the challenges and choose migration.

Requirements for sustainable Future

Action must be taken at the community, legislative and executive levels. Programs on the ground must be immediately launched, so as to reassure Christians in the Nineveh Plain that they are real participants in the region’s administrative and political decision-making.

Self-Community

- With the dispersed visions and efforts, contradiction and disagreement in many issues caused by the internal struggle within Christian community, it is necessary to launch and commit initiatives and organised frameworks to coordinate the political effort between the Christian political parties, on the one hand, and between them and the church references, on the other. They must agree on common issues and reduce differences and disagreements.

- Because current and future big political forces (Shia, Kurdish and Sunni) influence the future and structure of the political, administrative, and security administration of the Nineveh Plains, it is necessary to work on building political partnerships with these forces to serve a stable, participatory future among its components. With the demographic facts on the Nineveh Plains and its extensions in the Kurdistan region, partnerships with Kurdish forces are vital and positive. To achieve these alliances, especially the Kurdistan ones, the Christian political forces must change the populist, political discourse and Kurdish phobia.

- It is very important to apply Article 140 of the Constitution on the annexation and continuity of the Nineveh Plains with Kurdistan Iraq. The fragile Christian demography throughout Iraq cannot be divided into two separate demographics, each governed by a different constitution, legislations, administrative boundaries, and a different cultural and community atmosphere, especially as the administrative boundaries between KRI and the central Iraqi state will likely become a border between two states.

- It is very important to activate the economically and academically rich large Christian diaspora to invest its resources and potential in economic, educational and sustainable development program. Moreover, mechanisms and institutional frameworks must be developed to guarantee the professionalism and sustainability of these activities.

- While the declining Christian demography cannot be restored, the diaspora’s resources and network of institutional relations with churches and international organisations can launch and operate Christian initiatives and institutions that serve the entire Nineveh Plains. This could strengthen the Christian’s role in partnerships and social solidarity and compensate for the lost Christian demography.

Local Community

- A dialogue space should be launched to address issues of religious divisions and recommend positive religious discourse that avoids inciting hatred.

- Civil society should initiate programs of peaceful coexistence in which all community components, especially youth, participate in such activities as religious and national festivals, sports, artistic endeavours and media.

- Local administrative councils with secure financial resources could liberate communities from the control of both political parties and the central administration of the Nineveh governorate.

- The district or sub-district councils should determine programs and services in the centres of districts and sub-districts. This is greatly important for Christians throughout the Nineveh Plains, and the Yazidis in Baashiqa. While Christians constitute the absolute majority in Qaraqosh (the centre of Hamdaniyah) and Yazidis in the centre of Baaşhiqa, for example, the Christians in the district of Hamdaniyah and Yazidi in the sub-district of entire Baashiqa (centre and villages) are the minority. When Christians are a minority in the district council or the area, the majority ethnic group of the centre of the district or the sub-district can reject their programmes. For example, the district council of Hamdaniya rejected a request to build a convent for nuns in Qaraqosh. Similarly, the council in the sub-district of Bartilla, with a Muslim majority, rejected the allocation of land to build a church in the centre of Bartilla, the Christian city. Administrative decisions can assist in the demographic change; for example, the council of the sub-district of Bartilla built a residential complex in Bartilla, despite the Bartilla Christian community disapproval because of concern over demographic change.

National Iraq

- The Sunni Arabs must note the cumulative backgrounds and the context of the tragedy carried out by ISIS, addressing the roots of the tragedy and seek an atmosphere of acceptance, participation and coexistence.

- A serious national debate must be launched to study the tragedy, its causes, why and how it happened and preventative measures that prevent its recurrence. This is crucially important not only for justice for the victims, but also to reassure future generations that it will not recur. Laws must guarantee transitional justice and criminalise the discourse of hatred.

- All militias must be dismantled or pulled out of the Nineveh Plains. Public safety issues must be transferred to the security services and local police. In addition, in the short and medium-term, joint units between the Peshmerga and the Iraqi army, under control of the international coalition, will give a sense of demographic, social, and political security.

- A time limit must be set to implement the constitutional Article 140 under the supervision of the United Nations and the international community. In this context, adopt the 1957 census, because it is the only professional census conducted in stable political and security conditions without political agendas.

- When applying Article 140, the referendum must be held at level of the city and not the administrative unit. Christians are not a majority in any administrative units of the Nineveh Plains (both at the level of the district or sub-district), while they form a good or absolute majority in most cities where they live.

- The Nineveh Plains Province Formation Project must be adopted. It gives the components of the Nineveh Plains the power of administrative decision, economic planning and security control over their regions, and gives them a feeling and confidence in their role in building the future of their generations. If the governorate cannot be formed due to the political conflicts of the influential forces, it is important to annex the Christian and Yezidi demographics in the Nineveh Plains with Dohuk Governorate in order to ensure and strengthen the demographic connection.

- Because the central government is almost completely absent in the reconstruction programs of the Nineveh Plains, it must launch an adequately funded, special program to reconstruct, rehabilitate, and develop infrastructure and services in the Nineveh Plains.

- Reassuring messages must be sent from the central executive and administrative authorities, Nineveh governorate or from the various ministries and departments to the components of the Nineveh Plains. These messages should include granting them priority in managing government departments (health, education, services) and avoid provoking any of the religious, sectarian, or national components.

- National-level initiatives should recognise religious, sectarian and national components and respect their role in the history and civilisation of Iraq. This will have a positive role in building the national identity through cross-affiliations. For example, naming residential neighbourhoods, streets, schools, institutions in different Iraqi cities with names of personalities of different components would build bridges between these components. Also, identifying a national holiday for each Iraqi component will have a significantly positive impact on the recognition, coexistence, and mutual respect between these components.

International

- The international community should combat terrorism and dry up the sources of funding cross-border, systematic violence against religious minorities.

- International forces should recognise genocidal crimes and draw all legal, moral, and material consequences and implications.

- The international community and its institutions or influential countries must force the Iraqi federal government and KRI to commit to respecting human and minority rights in any political, economic, or military support programs.

- International, European or American office should be established to monitor the situation of minorities in the Nineveh Plains and submit periodic reports.

- A small Marshall Project should be launched for the reconstruction and economic development of the region.

- Institutional and community initiatives should support local civil society institutions and programs for peaceful coexistence.

We might be helpless, but never hopeless.

Christian Assyrians, regardless of their ethic nomenclature and church affiliation, are indigenous people of Mesopotamia, the Iraq of today, and they have had, throughout history, a distinguished role that surpassed the country’s borders to serve various aspects of humanity. This role includes extending bridges, communication, and dialogue on ideology, culture, and science between East and West.

Their existence is threatened today because of what they were. They are still subjected to a well-planned campaign aimed to eradicate their existence from the Iraqi national memory and physically remove them from the land of their ancestors. This campaign utilises different means starting with the constitution and continuing with legislation, curricula, religious bigotry, and systematic physical removal of individuals and communities.

Today, the requirements to protect their existence in their homeland surpasses their capacity. Therefore, that protection becomes a collective responsibility of the Iraqi state and international actors. They suffer from a violation of international treaties set forth to protect human, social, and minority rights.

Today, the Assyrian Christians, after becoming a marginalised minority in their homeland, live on the hope of a future that will guarantee justice and dignity, for they, regardless of what they went through, still believe in that hope. We, Mesopotamians Assyrian Christians in Mesopotamia might be helpless but never hopeless. However, it is a conditional hope.

Let us keep our moral commitment in supporting and practicing the actions on the ground To Keep the Hope Alive[19].